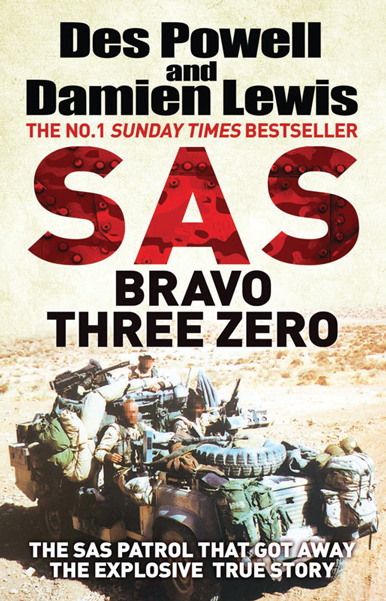

SAS BRAVO THREE ZERO

When I first met SAS veteran Des Powell and author Damien Lewis at National Army Museum, I was not looking for a story, I was just enjoying the first public event I managed to get after the lockdown, the launch of their new book SAS BRAVO THREE ZERO. Later on, while reading here and there from the book and trying to remember from the other books written about the famous Bravo mission from 30 years ago, I realized not only that I wanted to know more, but that I also wanted to share the story of this mission with the rest of you.

And so there I was having a chat with Des Powell about how the collaboration with Damien Lewis and the book came about and about the mission itself.

Like all the great things, the idea of the book started quite simply, as Des put it.

A guy named Paul Hughes introduced Damien and me. He was talking to me one day in his garden and he asked me, what have you been involved in? I only just managed to mention Bravo 30 and I didn’t even tell him the story. I just mentioned it. He got in touch with Damien and mentioned to Damien about me. And then one day Paul said we’re going to have a meeting with Damien Lewis, and I said, who is Damien Lewis? When we met it, Damien said that the story was interesting because he didn’t know that there were three patrols, Bravo One, Two and Three. Damien approached me and said that he’d like to write the story. Was I willing? And that is really how it came about.

And as Damien mentioned, when I heard he was on the Bravo Three Zero patrol, the sister patrol to the famous one, I was hooked. I’d always known of the Bravo Two Zero patrol – it’s a famous SAS mission. I never knew there were two other Bravo – B Squadron – patrols, Bravo One and Bravo Three. Just that was amazing – it made the story stand out.

And generate a lot of questions about the mission and what happened to the other two patrols, knowing the ill-fated Bravo Two patrol story.

One of those questions, and the next one I ask Des, is naming the most challenging moment his team experienced on the ground.

Probably the hardest thing was one evening when we were on the ground, having trouble sending messages over on the radio. But we managed to kind of decipher certain messages and we were almost sure that Bravo Two Zero was in trouble and that some guys had possibly died that evening. Not only from B20 but also from the other patrols with the other two squadrons coming up behind us. Two or three days we knew guys had died, we knew guys had possibly been injured, and guys were on the run. And it was frustrating for us because we weren’t in a position to do anything. Simply because we didn’t know where they were, and we couldn’t send any messages by radio. Plus it was snowing as well. It started snowing. So we were going down with hypothermia and we knew that guys had possibly died as well. So yes, those two or three evenings, they were very, very physical but also mentally draining as well.

And the best, the most rewarding moment from the mission?

Probably when we returned, we were surprised to find out that all our radio messages were being received and also to find out that our mission had been successful. They found the Scud sites and managed to bring in the airstrikes; our messages have been received and understood. We actually thought that our mission had possibly failed. Only when we got back, we learn we had been successful. So it was quite a very good, gratifying feeling. Not only did everyone get back safe, but we have been successful within our mission.

So we have the bad and the good moments, what about the funniest ones?

Just before we went on the mission, we were at an airbase in Saudi Arabia called Al-Jouf, and we were in a vehicle and as we were driving around the airport, we had a collision and we lost a wheel of the vehicle. But the vehicle was still able to drive on three wheels. And what we did? We went round to see the SEALs, the American SEAL teams. And we turned up in this vehicle with three wheels and asked if we could have ammunition, food, ration packs. And there was a talk about the vehicle, as you can imagine. We turned up, the SAS, in a vehicle still driving with three wheels and we came to see the SEALs asking them for food. And they’re saying, what is it with you guys? From start, you come here, you don’t have any equipment, or food, or ammunition. Plus, you turn up in a vehicle that’s only got three wheels. You guys are not gonna do any good if you’re gonna go behind enemy lines, you know.’ I think that’s quite typical SAS. We don’t ask for anything, we turn up with nothing at all and we get the job done.

When I asked Damien Lewis to highlight one episode from the mission, he picked the one when they are compromised by the enemy, and they try to bug-out – escape – in their two shockingly-badly-equipped Land Rovers, and one won’t even start. So they have to use a chain strung between the two, one dragging the other out, as they try to speed through the snow-bound desert to escape from the enemy. Utterly desperate.

And with these last answers, I should have thanked Des and finished the interview, as I had taken quite a chunk of his time. But I had to keep a promise. So while deciding if I should do the story, I asked the guys and gals from a tabbing community what it would be the just one question they will ask a former UK special forces operator. I explained all to Des, and he gladly told me to fire away.

What is the most difficult part of SOF training and what did you learn about yourself during and after the training?

The SAS selection training is in three parts. The first part is the hill phase and the navigation tabs. The middle part is the jungle phase and the last part is the escape and evasion phase. So over six months is split into three phases. The most difficult one, I think that most guys find it also, is the middle phase, the jungle. So on selection, because the jungle is such a harsh environment, they keep that as a tester.

For example, you go out, either to the jungle of Belize or Brunei, I’ve been to Brunei, and it’s an environment that doesn’t suit everyone. For a start is hard, it’s sweaty, you have got snakes, insects, and animals. You have to live out in the jungle for about six weeks or. You only have fresh food one day a week. You’re living on rations pack, you’re outside all that time, you have to learn to live off the land. You have to learn navigation, how to sleep in hammocks. They take you in helicopters and land you right in the middle of the jungle with two weeks walk to anywhere and that is your selection process and it’s a very, very hard environment. You learn a lot about yourself. You must have discipline, 100% discipline. You have water, you have shelter, and you have food in the jungle, but you’ve got to work hard every single day to get them. You’ve gotta keep yourself clean. You’ve got to eat properly. You’ve got to work hard. Every single day. Plus it’s a very, very scary environment. It’s not for everyone. But of course, that’s why they put in place in selection.

How do you ‘hold on’ in difficult times?

I think the one thing that the special forces guys are very good at is mental discipline. Is having a very strong mind disposition, if you like. Because you have always worked in difficult times, like within the regiment for example. So, therefore, whenever you come across a difficult situation, you know that that situation is not gonna last forever. So we have this mind discipline where we say right, let’s just see this through, and let’s be strong, let’s stay disciplined and it will pass. Other people who don’t have this strong mind discipline start to doubt, I can’t do this, it’s too hard, I’m too tired, it’s too cold, too hot. Instead of just saying hang on, I’ve done hard things like this before, I just need to see it through. I just need to be disciplined and time will pass. So I think special forces operators have this strong mind discipline to see the task through to the end.

Usually, special forces operators have grown up in broken homes, usually the dangle on the edge. If you weren’t military and SF, which direction would you see yourself going?

I was very very lucky. Actually, I come from a home that had my mother and father looking after me. I realized that a lot of people don’t come from a good home. I come from a place called Sheffield which is a big city and it’s very easy to go off the rails if you want to go to the bad side. I had a mother and father who loved me very much and made sure that I did the right thing, I went to school, and I didn’t hang around with the wrong crowd. My grandfather had been in the Second World War, so he was quite a disciplined guy and my father had been in national service, so both of those guys had a background of being in the military. I was probably exposed to that discipline from a very early age. I could see that there was a respect for my grandfather, and I could see the respect that my grandfather gave to my father, one being in the Second World War, one being in national service. So I think I was kept on the straight and narrow because of that.

How does your time training for and serving in the SF world help you today in your Civvy St, and how does it hinder you?

In fact, I don’t think there’s anything negative about it. Everything that I’ve learned in the military has helped me within this civilian world. For example, I have a morning routine, I have an afternoon routine and I have an evening routine too. I know most people that get up out of bed and just hit their day. I think it comes down to having good habits and good routines. Being able to follow through on the things that you need to do on a day to day, week to week, month to month. There are four things in life that you need to do if you want everything. One is hard work, so you’ve got to work hard at everything. Second one is consistency. You got to consistently work hard or focus or move forward to something. The third one is focus. Being able to focus on the job at hand, and the 4th one is to have discipline. If you have those four things that you find in the military and then blend that into Civvy St and have good habits that follow them, I don’t think you will have much problems at all.

What should my average pace be with loaded Bergen? No military experience, but looking into taking on a challenge next year.

If he’s a pure beginner, has no experience whatsoever, and I always say this to people, don’t go by the watch. Get used to carrying the weight, it doesn’t have to be 35lbs, but make sure that you get used to the correct boots, the correct clothing, the correct Bergen. And just get used to the environment because the most challenging thing is the elements, the wind, the rain, the cold, the snow and you’ve got to have the right equipment. You got the right boots and cold weather clothing and got used to carrying the weight. Just get used to walking over distances, a couple of hours and then three hours, four hours and so forth. Get used to good map reading techniques. Get used to being out in the elements and just comfortable with what you’re doing. Because you start to get aches and pains and have injuries with your ankles and knees. I call it getting acquired to the hills. You’ve gotta get used to the hill work. Just get used to your body getting fitter and fitter. And as you get fitter, you find that you naturally walk faster. And getting used to being outside in the elements. When people ask me, what’s the hardest physical thing I’ve done, I go, being outside in the cold, the wind, the rain and the snow. Fighting the elements takes more energy than working in the gym. And that’s mainly because your body is trying to stay warm. So just get acquired to the hills, get used to your fitness, get used to carrying equipment and then you can start to worry about how fast you should tab.

Interview by Marcella Dragan; Images courtesy of Des Powell; Published in Tactica Magazine #14